As at 30 March 2022

Author: Gavyn Davies, Executive Chairman

After years of deliberation, the new framework was introduced in 2020 to cope with the dominant problem faced in the previous decade. This was so-called “secular stagnation” in which a return to the zero lower bound (ZLB) for policy interest rates seemed to be the main problem facing the central banks. The new strategy featured a maximum employment target, combined with an average inflation target (AIT), both of which were intended to diminish the risk of getting stuck in a deflationary liquidity trap at the ZLB.

Within months, this framework became redundant. Inflation rose sharply throughout 2021, and this phenomenon did not prove to be “transitory” as expected by the Fed. The CPI level soon exceeded the path expected under the AIT, but there was no policy response from the Fed.

The Fed and other central banks now need to decide how much of this unexpected increase in the price level they should permanently accommodate. Under an AIT, it would be expected that part or all of this price shock would be followed by a period of inflation below 2%, so that in the long run inflation would remain at 2% on average.

However, there is no sign that the Fed wants to do this in practice. It seems far more likely that they will accommodate most or all of the price shock, because the cost of reversing the shock would probably be a severe recession.

This means that they will allow the annual inflation rate to return only gradually to 2%, allowing a permanent increase both in the price level and the long run average inflation rate, compared to what was expected in 2020.

However, they are likely to tighten monetary policy enough to ensure (or hope) that forward inflation expectations remain close to their 2% target, despite the very large miss to the target in 2022-24.

Author: Gavyn Davies, Chairman, Fulcrum Asset Management, 30 March 2022

THE FED’S 2020 POLICY FRAMEWORK

Fed Chairman Jerome Powell announced a major review of the central bank’s policy framework in November 2018. When the results were announced in August 2020, there were two key features of the new approach:

- The FOMC’s statement claimed that “a robust job market can be sustained without causing an unwelcome increase in inflation”, implying that a “policy decision will be informed by “assessments of the shortfalls of employment from its maximum level”.

- The FOMC maintained a formal target for inflation, but it adjusted its strategy for achieving its longer-run inflation goal of 2% by noting that it “seeks to achieve inflation that averages 2% over time.” To this end, the revised statement states that “following periods when inflation has been running persistently below 2%, appropriate monetary policy will likely aim to achieve inflation moderately above 2% for some time.”

Although these statements could be argued to have remained compatible with the “dual mandate” imposed on the Fed by Congress, they placed much more emphasis on achieving maximum employment than before and promised that inflation could exceed 2% for “temporary” periods if this were required to compensate for earlier shortfalls in the price level from the target path.

Wisely, the Fed allowed itself room for manoeuvre in running this strategy in practice:

- Although it probably intended the AIT to apply symmetrically in the case of shortfalls or overshoots in the price level, the Fed did not specifically point out that it would compensate for any period in which inflation had exceeded 2% by running inflation below 2% in a subsequent period.

- The FOMC deliberately left open the exact definition of the period to be applied to the target, allowing this to be determined by circumstances.

- The FOMC explained that, if its inflation and employment objectives pointed in different directions, then it would consider “the employment shortfalls and inflation deviations and the potentially different time horizons over which employment and inflation are projected to return to levels judged consistent with its mandate”.

These get-out-of-jail clauses will be important in handling the present situation. However, they are not sufficient to hide the fact that the 2% AIT has now been greatly exceeded since 2020, leaving the Fed needing to explain whether it intends to compensate for this overshoot by running inflation below 2% for a considerable period in the future. Failure to do this would imply that the central bank will have accepted a permanent jump in the price level, relative to the path it originally intended when it introduced the AIT.

CALCULATIONS FOR THE FED’S AVERAGE INFLATION TARGET

When the FOMC introduced its new average inflation target in 2020, it did not specify either the starting date for the target period, or the length of the period, either backwards or forwards, that would be used to calculate the monthly PCE price levels that would be considered compliant with its target framework. It argued that there would be no mathematical formula from which to calculate the new target. This ambiguity was probably intended, but it leaves the approach open to interpretation and may reduce the credibility of the entire framework.

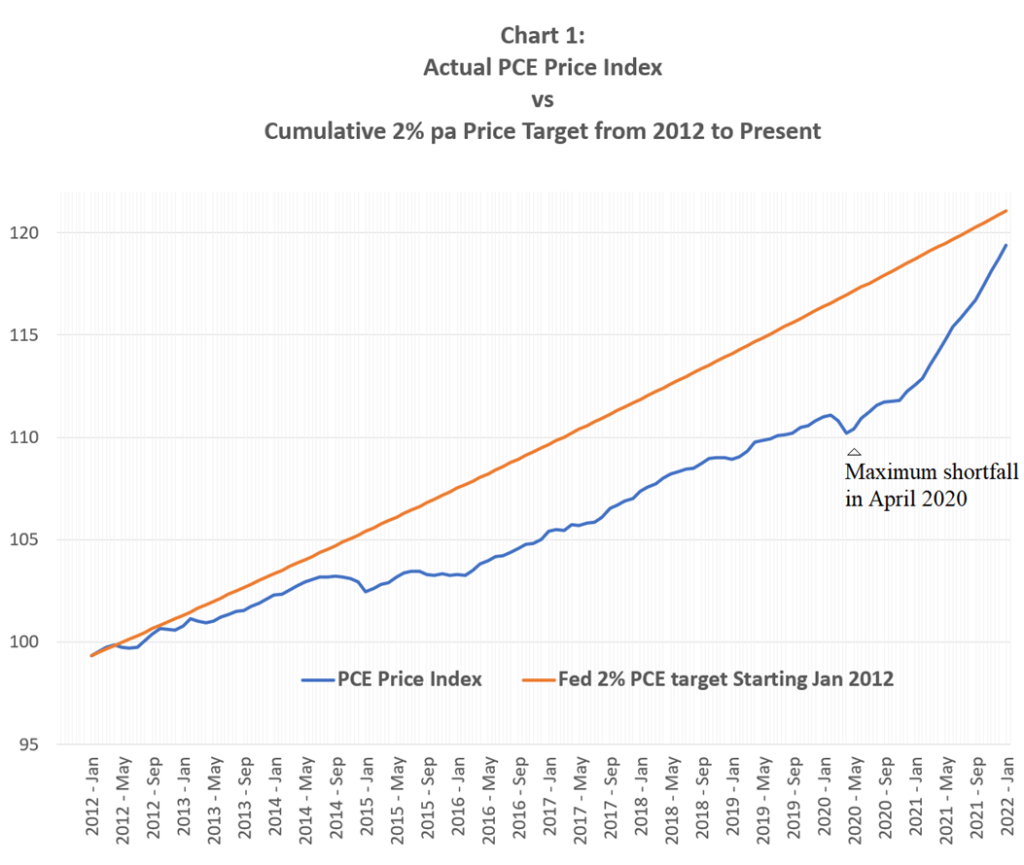

In interpreting the new target, it is critical to select the base date which applies to the average 2% inflation rate as new data come in. One approach would be to choose January 2012, when the FOMC officially adopted an inflation objective for the first time.

Using this start date, the actual rate of inflation (and therefore the price level) persistently fell short of the 2% objective, as shown in Chart 1. This shortfall continued to widen until April 2020, when it reached 5.7%. Since then, the gap has been narrowing, as inflation has accelerated to above 2%. In the latest PCE data for January 2022, the price level is 1.4% below the level implied by the 2% average inflation rate over the entire period.

Source: Fulcrum Asset Management LLP

The Fed could claim that this is only a negligible miss to its AIT, if measured over a backward horizon extended to the beginning of the original inflation target, which happens to be exactly a decade long. This would imply that the entire increase in inflation in recent months is deemed to be consistent with this version of the AIT.

However, such an elastic approach to the definition of the target period seems to be stretching credulity towards breaking point. If this had been the intention when the new framework was announced, surely the FOMC might have mentioned it at the time?

A different definition of the AIT target would be to start at the time when it was announced (August 2020) and assume that the Fed will aim to keep the PCE index on a 2% average inflation rate, moving forward from that date. This seems consistent with the forward-looking language in Chair Powell’s speech when the AIT was introduced:

“We will seek to achieve inflation that averages 2 percent over time…. Of course, if excessive inflationary pressures were to build or inflation expectations were to ratchet above levels consistent with our goal, we would not hesitate to act”.

In his FOMC press conference in September 2020, Chair Powell spelled out the inflation objective as follows:

“With inflation running persistently below 2 percent, we will aim to achieve inflation moderately above 2 percent for some time so that inflation averages 2 percent over time… We would like to see, and we will conduct policies so that inflation moves, for some time, moderately above 2 percent. These won’t be large overshoots, and they won’t be permanent but to help anchor inflation expectations at 2 percent”.

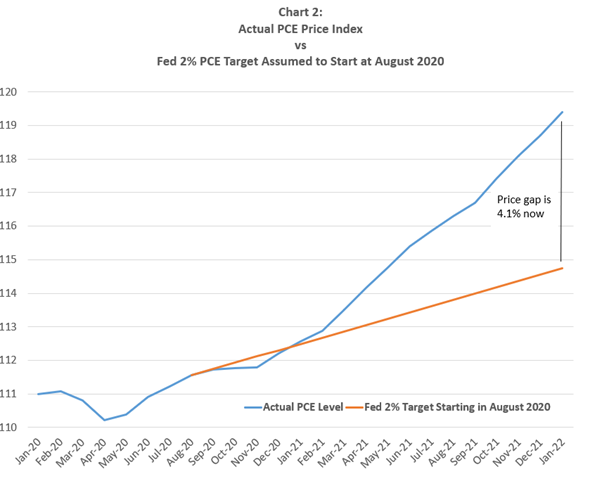

Former Fed Vice Chair Richard Clarida was more specific about how he interpreted the AIT when he was in office. For example, in a speech on 8 November 2021, he provided calculations for inflation that used August 2020 as a start date:

“Commencing policy normalization in 2023 would…be entirely consistent with our new flexible average inflation targeting framework. I note that under the June SEP median of modal projections, annualized PCE inflation since the new framework was adopted in August 2020 is projected to average 2.6 percent through year-end 2022 and 2.5 percent through year-end 2023”.

These statements suggest that the leadership of the Fed believed that a moderate increase in inflation above the 2% target for 2 or 3 years after August 2020 would be permissable under their interpretation of the AIT. However, this does not seem consistent with the much higher annualised inflation rate that has occurred since then, as shown in Chart 2. Up to the present time, the price cap starting from August 2020 stands at 4.1%.

Source: Fulcrum Asset Management LLP

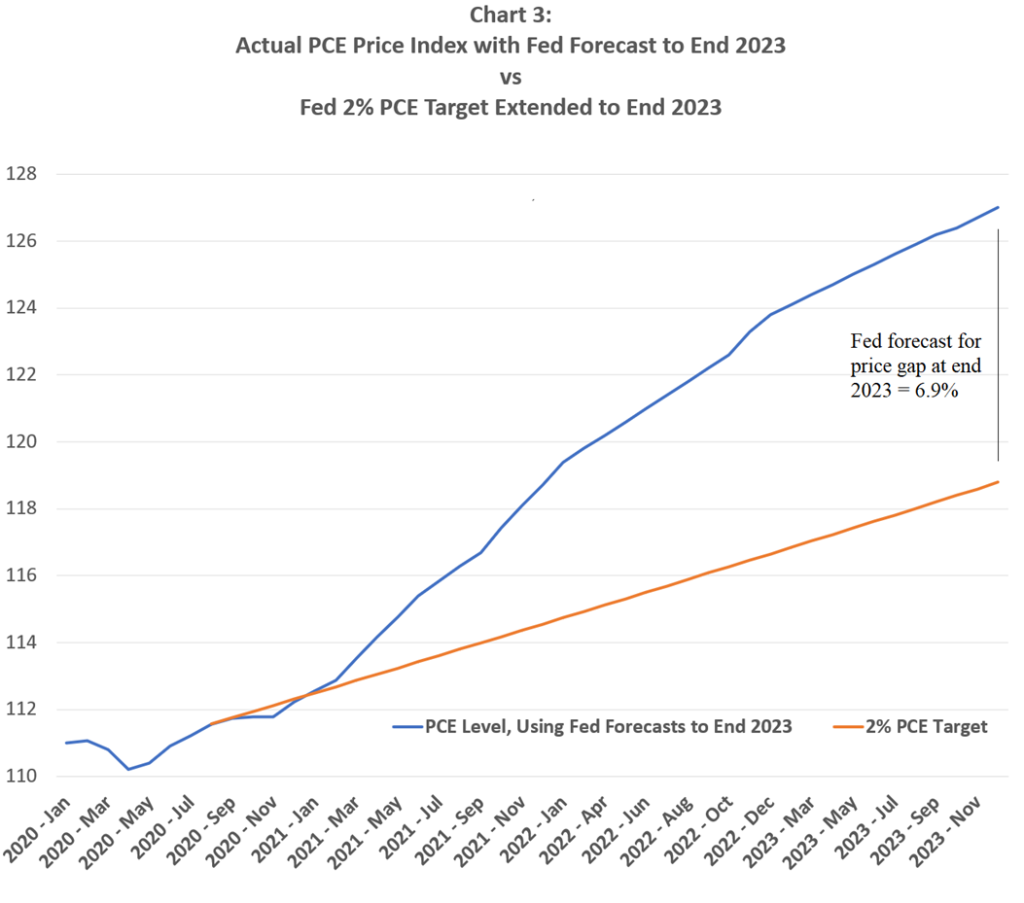

Furthermore, as shown in Chart 3, the FOMC now expects the overshoot in the price level, relative to the 2% average target, to increase further in 2022 and 2023. The FOMC’s median inflation forecast shows that, by the end of next year, the annualised inflation rate will have averaged 4.1% for 3 years and four months, or one third of a decade.

By that stage, the PCE price level will be about 7 percentage points above the level implied by an average inflation target running at 2% annualised since the framework was announced. That would represent a substantial overshoot relative to any definition of the target period for the AIT, and many independent forecasters expect the overshoot to be even larger than shown by the FOMC in their latest projections to the end of 2023.

This deterioration in inflation performance happened suddenly from mid-2021 onwards and was recognised by the FOMC around November 2021. It of course explains the rapid shift to far more hawkish policy that has occurred since last December.

Source: Fulcrum Asset Management LLP

WHERE NEXT FOR THE FED’S INFLATION STRATEGY?

In his latest pronouncement on inflation and monetary policy on 21 March 2022, Chair Powell has admitted that the rise in inflation has been much greater and more persistent than forecasters, including the FOMC itself, expected. His conclusion was simple:

“My main message today is that…we will adjust policy as needed in order to ensure a return to price stability with a strong job market…Inflation is much too high. We have the necessary tools, and we will use them to restore price stability”.

The key for markets is how the FOMC chooses to define the “return to price stability” after a period in which inflation will have greatly exceeded 2% for a very long period.

Remarkably, Mr Powell did not mention the average inflation framework at all in his speech on “Restoring Price Stability”. So, we are left to speculate.

In his most recent FOMC press conference, Mr Powell said the following:

“The strong labor market is leading to wages moving up at ways that are not consistent with 2 percent inflation over time. And so, we need to use our tools to guide inflation back down to 2 percent”.

It seems from this and other remarks that the Chair is satisfied with an inflation path that gradually returns to 2%, even though he admits that it will take at least three more years to reach that objective, and even though this results in a path for the price level that is well above that strongly implied by the new framework announced in August 2020.

On the framework itself, Mr Powell said the following:

“Nothing in our new framework…has caused us to wait longer to raise interest rates. The framework is all about anchoring inflation expectations at 2 percent. We can’t blame the framework. It was a sudden, unexpected burst of inflation.”

It appears that the Chair regards the major innovation in monetary strategy undertaken on his watch to have been completely irrelevant to the inflation shock. It is true that the shock was in large part due to supply-side factors that are outside the Fed’s control. But they occurred at a time when the new framework had decided to boost aggregate demand relative to previous monetary strategies, thus leaving the economy more vulnerable to high inflation after adverse supply shocks.

Chair Powell now concedes that the Fed will need to slow the growth in demand in order to bring inflation down. However, there are limits to his willingness to slow the economy:

“We’re not going to let high inflation become entrenched. The costs of that would be too high. And we’re not going to wait so long that we have to do that. No one wants to have to really put restrictive monetary policy on in order to get inflation back down… So, frankly, the need is one of getting rates back up to more neutral levels as quickly as we practicably can”.

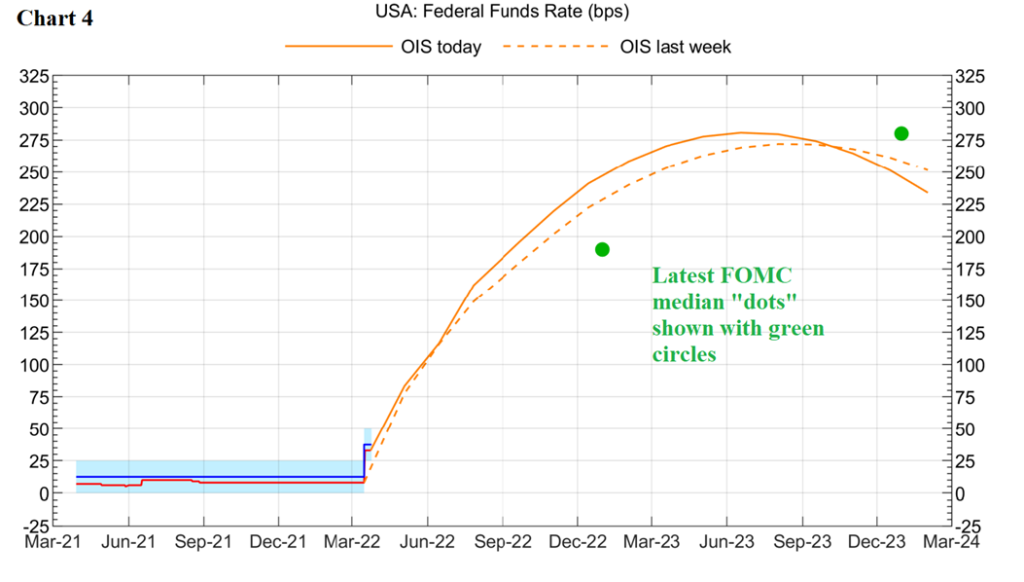

It therefore seems that the FOMC will move rapidly to return policy to “neutral”. This will probably involve at least one, and likely more than one, increase of 50bp in forthcoming policy meetings. When policy rates have exceeded the neutral level of about 2.5%, the Committee will think again about whether to tighten further.

The short-term interest rate (OIS) markets have now fully priced the expectation that the Fed will raise policy rates to 2.75% in the next 12 months (see Chart 4).

Source: Fulcrum Asset Management LLP

THE FORMATION OF PRICE EXPECTATIONS

With the forward markets now “pricing” the expectation that the FOMC will increase rates by more than shown in the Fed dots, the period of rapid upward adjustment in rate expectations may have ended for now. However, the really important question for markets is whether the end point for rates in this cycle will remain at around 2.75% or will eventually need to be much higher to bring inflation back down to 2%, and to keep long term inflation expectations around the Fed’s long-term target.

The outcome will depend to a large extent on how price expectations eventually react to the fact that the FOMC greatly downplayed its AIT when it was first tested by an upward inflation shock. It basically had two options as the price shock increased after mid 2021:

- The FOMC could have emphasised that the new AIT framework would remain intact, implying that a period of inflation below 2% would be eventually needed to bring the PCE price path back onto its long-term desired trajectory; or

- The FOMC could have passively accepted the increase in the level of prices caused by the supply shocks, promising only to bring the annual inflation rate back down to 2% after a long period of significant overshoots. This would mean that the price level, and the average inflation rate, would be permanently increased by the supply shocks.

At present, it seems clear that Chair Powell has decided to choose the latter option, which involves smaller sacrifices to output in the near term, but potentially larger increases in inflation expectations in the longer term.

He will no doubt explain this decision by arguing that the combination of a pandemic and a war in mainland Europe represents a unique set of circumstances which justifies a permanent rise in the American consumer price level. He will claim, with some justification, that such a set of events is unlikely to happen again, so this does not constitute a reason to doubt the Fed’s commitment to a 2% inflation target when normal circumstances return to the world economy.

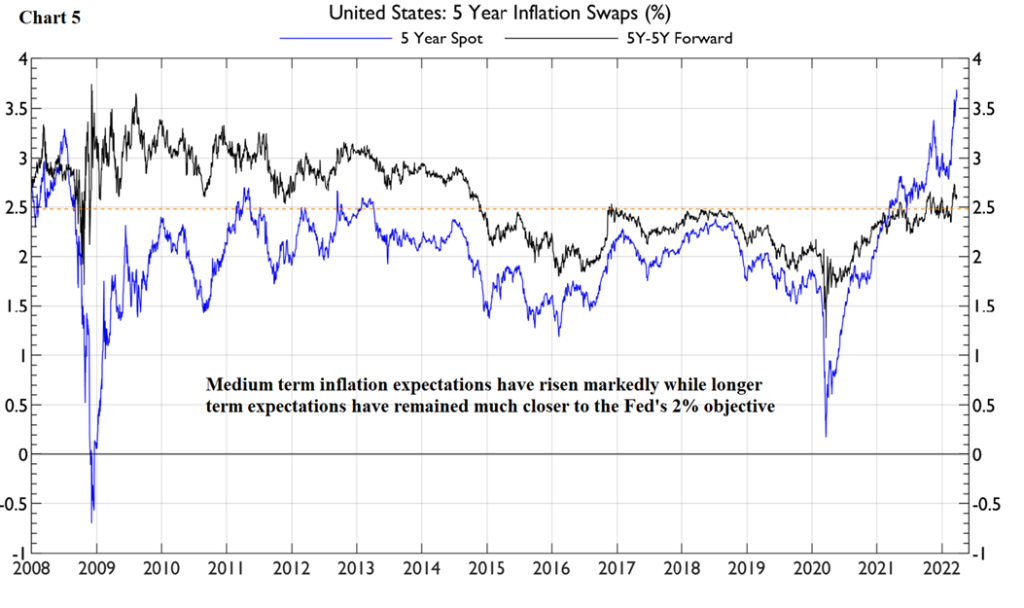

So far, as shown in Chart 5, the markets seem to have accepted that inflation will rise substantially in the medium term (up to 5 years ahead) but will remain fairly close to the Fed’s 2% long run target in the much longer term (between 5 and 10 years from now). That is what the Fed wants.

However, the story of the 2020s inflation shock is far from over. Many respected economists, including Lawrence Summers and Olivier Blanchard, are warning of the risks that inflation expectations might become detached from the 2% objective, causing a repeat of the economic tribulations seen in the 1970s and early 1980s. We share their concerns.

The Fed’s credibility is not completely guaranteed, and its framework needs to be redefined and renewed.

Source: Fulcrum Asset Management LLP