Introduction

Monetary policy as we know it has become redundant. Central banks’ golden era is probably over.

When former US Treasury secretary Lawrence Summers delivered his famous address on the return of secular stagnation at the IMF in 2013, he revived interest in a Keynesian construct that had fallen into disuse since the 1940s. He argued that a chronic excess of savings, relative to capital investment, may be developing in the global economy, forcing long-term interest rates down and threatening a persistent shortage of demand.

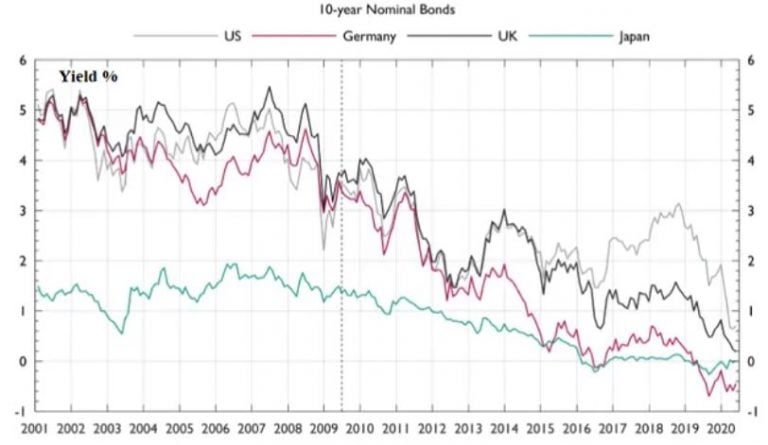

Since 2013, there have been brief periods of strong output growth in the large economies, suggesting that the risks of secular stagnation were abating. But these cyclical upswings proved temporary and the trend decline in global long-term interest rates towards zero was never ended.

On top of these deflationary trends, the Covid-19 lockdowns have caused a seismic shock in all the big economies. In a recent Princeton Bendheim webinar, Mr Summers argues that this will trigger structural responses from households and businesses that will strengthen the forces of stagnation. If he is right, the consequences for macroeconomic policymakers and asset managers will be profound.

What are these changes in behaviour? Mr Summers believes risk aversion in the private sector will increase permanently, leading to more precautionary savings by households, and less investment by businesses. As he puts it, “just in case will replace just in time”, with the private sector wanting to hold greater financial reserves in case of further shocks to globalised markets. There may also be a long-lasting hit to labour utilisation — the productive deployment of people of working age — and reductions in consumer spending in sectors affected by social distancing until an effective vaccine is found.

Whether or not Mr Summers is right about the long-lasting effects of coronavirus, the underlying trend towards secular stagnation has been manifest for two decades. There seems no reason for it to reverse itself spontaneously.

Now policy interest rates in all the major economies are at or below the zero lower bound, monetary policy as we know it has become redundant. Central banks still have an important role to play in providing emergency injections of liquidity in crises and in regulating financial institutions, but their golden era is probably at an end.

A permanent state in which the equilibrium nominal interest rate throughout the developed world is at or below the central bank policy rate is, to put it mildly, really worrying.

There are three possible consequences of this.

The first is that the world could be stuck at zero. All the advanced economies may follow the example of Japan since 2016, with interest rates across the entire yield curve stuck at zero, and fiscal policy battling against a continuous rise in government debt ratios. For asset markets, this would represent a low-return world, with demand management becoming increasingly hamstrung in recurring recessions.

With the second, we could have permanent fiscal stimulus and rising debt. Before the full effects of the virus became apparent, Paul Krugman suggested that the US should permanently increase public investment and the budget deficit by 2 per cent of gross domestic product, with the debt ratio eventually rising to 200 per cent of GDP. This would increase equilibrium interest rates, raising the average level of policy rates and bond yields. The yield curve would shift higher and adopt a more normal upward slope, allowing more scope for easing during recessions.

By reversing the trend decline in interest rates, this policy may result in an immediate period of negative returns for both bonds and equities, though the long-term effects are less clear.

And the third could give us very negative interest rates. Japan and the eurozone have attempted to increase scope for active monetary policy by reducing policy rates slightly below zero, eventually dragging bond yields into negative territory. However, as Kenneth Rogoff has argued, this policy could only succeed if pursued far more aggressively, taking policy rates to minus 3 per cent, or even lower, in recessions. By extending the decades-long downward trend in interest rates, this approach would probably prolong high returns from both bonds and equities.

The political feasibility of these extremely radical fiscal and monetary policy changes seems highly questionable. But if Mr Summers is right about the deepening of secular stagnation, such reforms might be needed to avoid Japanese-style deflation in Europe, and even the US.

Bond yields head to zero or below Real bond yields in all the advanced economies on average have been close to, or below, zero since 2015

Nominal bond yields have also now reached almost zero, even in the US. The recent combination of zero yields in both nominal and real terms seems novel, though Paul Schmelzing argues that real rates have in fact been trending lower for seven centuries!

Source: This note is based on material which appeared in an article by Gavyn Davies published in the Financial Times on 31 May 2020.

This material is for your information only and is not intended to be used by anyone other than you. It is directed at professional clients and eligible counterparties only and is not intended for retail clients. The information contained herein should not be regarded as an offer to sell or as a solicitation of an offer to buy any financial products, including an interest in a fund, or an official confirmation of any transaction. Any such offer or solicitation will be made to qualified investors only by means of an offering memorandum and related subscription agreement. The material is intended only to facilitate your discussions with Fulcrum Asset Management as to the opportunities available to our clients. The given material is subject to change and, although based upon information which we consider reliable, it is not guaranteed as to accuracy or completeness and it should not be relied upon as such. The material is not intended to be used as a general guide to investing, or as a source of any specific investment recommendations, and makes no implied or express recommendations concerning the manner in which any client’s account should or would be handled, as appropriate investment strategies depend upon client’s investment objectives. Funds managed by Fulcrum Asset Management LLP are in general managed using quantitative models though, where this is the case, Fulcrum Asset Management LLP can and do make discretionary decisions on a frequent basis and reserves the right to do so at any point. Past performance is not a guide to future performance. Future returns are not guaranteed and a loss of principal may occur. Fulcrum Asset Management LLP is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority of the United Kingdom (No: 230683) and incorporated as a Limited Liability Partnership in England and Wales (No: OC306401) with its registered office at Marble Arch House, 66 Seymour Street, London, W1H 5BT. Fulcrum Asset Management LP is a wholly owned subsidiary of Fulcrum Asset Management LLP incorporated in the State of Delaware, operating from 350 Park Avenue, 13th Floor New York, NY 10022.

©2020 Fulcrum Asset Management LLP. All rights reserved

About the Author

Gavyn Davies

Gavyn Davies is Chairman of Fulcrum Asset Management and co-founder of Active Partners and Anthos Capital. He was the head of the global economics department at Goldman Sachs from 1987-2001 and Chairman of the BBC from 2001-2004. He has also served as an economic policy adviser in No 10 Downing Street, and an external adviser to the British Treasury. He is a visiting fellow at Balliol College, Oxford.