Introduction

Demand has outstripped supply since 2009 but the latest crisis may help to redress the balance.

One of the long-term consequences of the 2008 financial crisis was a lack of safe assets that could be used by institutions to store their wealth, meet regulatory requirements and provide collateral to borrow additional funds.

This problem has been identified as an important reason for low capital investment and the slow growth rate in the global economy in the past decade. It was also a prime cause of the European sovereign debt crisis, which peaked in 2012.

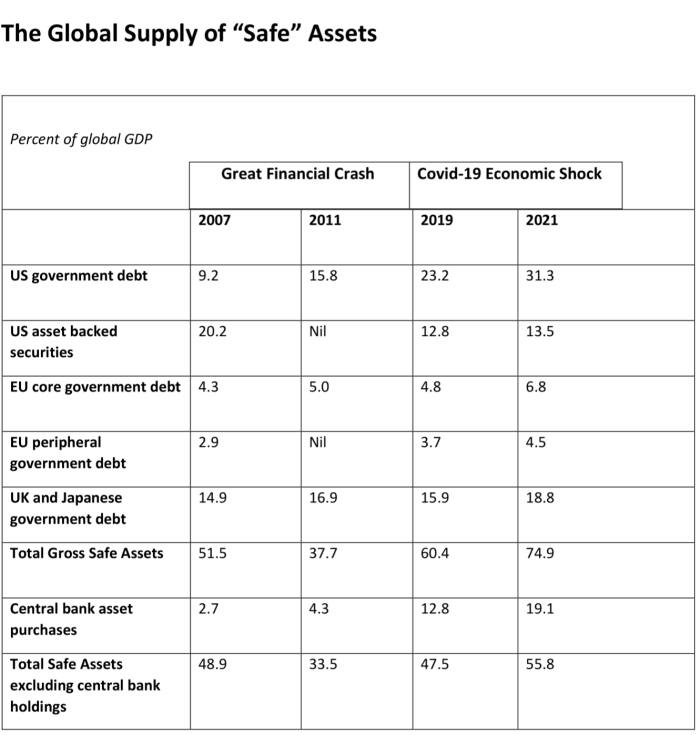

But a silver lining from the Covid-19 shock is that the policy response may actually alleviate the safe-asset shortage, according to new research by Fulcrum economists (see table). That’s because it will leave a legacy of much higher government debt in the most advanced economies, including the US, which is the main global source of these assets.

A safe asset is usually defined as a financial instrument that is unlikely to experience a big increase in default risk, even at the darkest times in the economic cycle. It is therefore a reliable source of liquidity when riskier assets suddenly lose value. It will often face inflation and interest rate risk, but usually not default risk.

Before 2008, the supply of high-grade government bonds in the advanced economies was restricted because budget deficits were declining. To meet demand, the private sector created AAA-rated tranches of mortgage and other credit products. But these products proved to be anything but safe, prompting a stampede into government bonds, especially US treasuries and German bonds, which were deemed immune from default risk. New banking regulations requiring them to increase their capital and liquidity buffers later made this outcome more permanent.

The definitions and assumptions used in this table are explained in full in a research note by Fulcrum economists

Why did this create a serious problem? In theory, since the price of government bonds is determined in a free market, a supply shortage would be expected to be eliminated by higher bond prices and therefore lower yields. This, indeed, happened, and after 2015 the US currency also appreciated, choking off excess demand for dollar-based assets.

The trouble for the world economy arose when bond yields in many economies approached zero, making it all but impossible to achieve the further decline in yields needed to rein in demand for safe assets.

Economists including Ricardo Caballero and Emmanuel Farhi say that in some models this can result in a “safety trap” that affects the global economy. This is a close cousin of the “liquidity trap” that appears in many New Keynesian models.

Because interest rates cannot fall enough to balance the supply and demand for safe assets, national income and wealth shrink to eliminate the excess demand for them.

Messrs Caballero and Farhi, along with Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas, suggest that the flight to safety increases the equity risk premium relative to safe assets, accounting for part of the weakness of capital expenditure in the advanced economies since 2009.

Given the potentially serious consequences of the safety trap, it would be alarming if the Covid-19 shock replicated the financial crisis by making the imbalance even worse — but this seems unlikely to happen. The rise in public debt, and so the supply of safe assets, will this time be both quicker and larger. In addition, the financial system has so far been more insulated from the shock, so it is less likely that the highest rated credit tranches in the US mortgage market will fall out of the category of safe assets.

Direct purchases of corporate credit and loans by the US Federal Reserve may protect the asset-backed securities market from widespread default. In the eurozone, the steps taken towards an EU-backed recovery bond should add to safe assets, instead of wiping them out.

This growing supply of safe assets could, however, be offset by rising demand. Central bank asset-purchase programmes will remove government bonds and the safest tranches of securitised credit products from the hands of the private sector.

In the longer term, the overall effects on bond yields will also be influenced by the impact of the Covid-19 shock on net private savings. According to research by Oxford Economics, which warned about the worrying trend in safe-asset supply just before the pandemic, a possible shift towards excess private savings and reduced investment after this recession could offset the initial improvements in safe-asset supply.

These longer-term effects are very hard to predict. The good news is that the Covid-19 recession will almost certainly increase the supply of safe assets in the immediate future, alleviating the problem as the global economy starts to recover.

Source: This note is based on material which appeared in an article by Gavyn Davies published in the Financial Times on 29 June 2020.

This material is for your information only and is not intended to be used by anyone other than you. It is directed at professional clients and eligible counterparties only and is not intended for retail clients. The information contained herein should not be regarded as an offer to sell or as a solicitation of an offer to buy any financial products, including an interest in a fund, or an official confirmation of any transaction. Any such offer or solicitation will be made to qualified investors only by means of an offering memorandum and related subscription agreement. The material is intended only to facilitate your discussions with Fulcrum Asset Management as to the opportunities available to our clients. The given material is subject to change and, although based upon information which we consider reliable, it is not guaranteed as to accuracy or completeness and it should not be relied upon as such. The material is not intended to be used as a general guide to investing, or as a source of any specific investment recommendations, and makes no implied or express recommendations concerning the manner in which any client’s account should or would be handled, as appropriate investment strategies depend upon client’s investment objectives. Funds managed by Fulcrum Asset Management LLP are in general managed using quantitative models though, where this is the case, Fulcrum Asset Management LLP can and do make discretionary decisions on a frequent basis and reserves the right to do so at any point. Past performance is not a guide to future performance. Future returns are not guaranteed and a loss of principal may occur. Fulcrum Asset Management LLP is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority of the United Kingdom (No: 230683) and incorporated as a Limited Liability Partnership in England and Wales (No: OC306401) with its registered office at Marble Arch House, 66 Seymour Street, London, W1H 5BT. Fulcrum Asset Management LP is a wholly owned subsidiary of Fulcrum Asset Management LLP incorporated in the State of Delaware, operating from 350 Park Avenue, 13th Floor New York, NY 10022.

©2020 Fulcrum Asset Management LLP. All rights reserved.

About the Author

Gavyn Davies

Gavyn Davies is Chairman of Fulcrum Asset Management and co-founder of Active Partners and Anthos Capital. He was the head of the global economics department at Goldman Sachs from 1987-2001 and Chairman of the BBC from 2001-2004. He has also served as an economic policy adviser in No 10 Downing Street, and an external adviser to the British Treasury. He is a visiting fellow at Balliol College, Oxford.